The Costs of Pursuing Impeachment

Removal of a political leader prior to the end of his or her term rarely serves as a positive indicator for the then-current state of affairs. Impeachment and removal of a president, for example, may be preferable in light of the president’s offending conduct, but it carries its own disruptive costs. The framers made it difficult to remove a president, one logically assumes, because they anticipated it would be worth bearing the destabilizing effects only to eradicate the most serious of damaging offenses to the country.

President Donald Trump is a historically unpopular president right now, so it is not surprising that many Americans (and other people) want him out of office as soon as possible. It also is easy to see how a perceived expediency and efficacy of removal through the impeachment process would offer a means to that end that the President’s opponents find attractive. In short, it looks to them like a get out of jail free card, a silver bullet that, in rapid fashion, will erase what they believe to be the source of their problems in one clean shot.

Like most governmental processes, impeachment and removal does not happen that quickly, though, as this timeline from President Bill Clinton’s administration reminds. It also is far from clear that sufficient congressional will exists to impeach the President at this time.

These practical hurdles do not seem to be of great concern to the impeachment proponents, who have seized on the President’s alleged connections with Russia as their best hope for his removal prior to the end of his first term, even if, as some have observed, the asserted nature of the improper Russian involvement has evolved over time.

The foregoing notwithstanding, it often seems as though the President’s critics have coalesced around impeachment as the singular aspirational focus of their opposition. In doing so, they ignore the day-to-day policy activities of the administration and Congress. While not necessarily evidencing the smooth operation expected of a more experienced administration, Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress are advancing certain agenda items likely to have lasting effect while the vocal opposition remains distracted with Russia. At some point, putting all of their eggs in one shoot-the-moon basket is likely to backfire on the President’s adversaries, even if they ultimately succeed. Upon review of the new tax bill, reauthorization of NSA surveillance laws, environmental regulation rollbacks, potential renergization of federal marijuana prosecution, and appointment of a dozen new federal judges, among other accomplishments, they might conclude that point is in the past.

Hypocratic Oath

It is possible to use the internet to commit a crime. For example, one could use a Silk Road-like website to acquire a controlled substance it is illegal to possess in one’s geographical jurisdiction, or simply use the web’s myriad means of communication to coordinate a financial fraud.

It also is possible to commit an internet crime. The social and commercial interactions that occur within the internet itself are subject to a sort of moral code, and, for all of the flexibility and fluidity the web as a virtual space would seem to offer, one of the highest internet crimes arises out of inconsistency. For many in this realm, there is no greater offense than to be indicted for the offense of hypocrisy. And, indeed, indictment and conviction are nearly simultaneous in this medium, with sentencing following quite swiftly thereafter.

The internet remembers all, or sufficiently all, anyway, to retain record of those off-color tweets you sent years before you took a public stand against others who said similar things, and when someone else finds those old tweets, man are you going to look silly. One of the things at which human brains excel is detecting patterns, and when the alleged hypocrite expresses something apparently inconsistent with his or her prior positions, a little nugget of pleasure releases inside those brains upon the presentation of the irrefutable evidence from the historical record. Guilty on the spot.

The web-seductiveness of exposing apparent hypocrites is so alluring that it makes it easy to forget that hypocrisy, for all its attendant failings, is a sort of derivative or second-level offense, and our obsession with rooting it out can obscure or overwhelm what often is a serious substantive problem underlying the procedural default. In that way, for example, we frequently focus on an evaluation of the authenticity of an entertainment personality’s expressed opposition to the mistreatment of women when we subsequently find that she or he previously engaged in similar (or maybe even not that similar, but, hey, close enough) mistreatment in the past, rather than the actually bad problem itself. (This also touches on why otherwise uninvolved people “coming out as” anti-rape, anti-Nazi, etc., contributes very little to the general good.) Sexual harassment in the workplace and racism in public policy are two very real and significant issues that require real, meaningful effort to address, and yet we are so easily distracted from this work by the thrill of hypocrite hunting.

In the context of last month’s Senate election in Alabama, in which Doug Jones ultimately defeated Roy Moore by a margin the narrowness of which made many uncomfortable, Jonah Goldberg wrote for the Los Angeles Times about the dangers of our national distraction:

This obsession with hypocrisy leads to a repugnant immorality. In an effort to defend members of their team, partisans end up defending the underlying behavior itself. After all, you can only be a hypocrite if you violate some principle you preach. If you ditch the principle, you can dodge the hypocrisy charge. We’re seeing this happen in real time with some of Moore’s defenders, just as we saw it with Clinton’s in the 1990s.

Jonah Goldberg, Taking harassment seriously also requires making serious distinctions, Los Angeles Times, Nov. 21, 2017.

Or, as another thoughtful observer put it in sometimes cruder terms:

Wishing everyone a safe and happy new year filled with a renewed focus and energy for addressing some of our real problems in 2018.

Toward Eternal Tonehenge

In the introduction to the seminal work entitled An Introduction to the Creation of Electroacoustic Music, Professor Sam Pellman wrote:

For thousands of years, the predominant medium of musical expression was the human voice. In the past few centuries, however, musical instruments have become increasingly important. The sophistication of these instruments has paralleled the development of technology in general. Early musical instruments were relatively simple devices constructed of wood or of the horns of animals. By the 19th century, the level of mechanical ingenuity had progressed to the point that remarkably clever instruments made of a wide variety of materials, including metals, could be perfected or invented. The piano is perhaps the best representative of the technology of that time. Modern wind and brass instruments, such as the saxophone and the trumpet, reached maturity during this time as well. One thing that all of these instruments had in common was that they depended on the power of human breath or the muscles of the arms to create the waves of sound that could be heard as music.

The preeminent technology of the 20th century has been electronic. It seems inevitable, therefore, that musical instruments would be developed that would apply the power of electricity and the control capabilities of electronics to the task of creating musical sounds. The field of scientific study that deals with the transformation of energy between electrical forms and acoustical forms is called electroacoustics. This term has been borrowed by musicians who use electronic instruments, so that their music has come to be known as electroacoustic music. Such music may consist of sounds that are produced naturally and then transformed electronically . . . or of sounds that are created synthetically, by oscillating electrical circuits . . . . Most typically, perhaps, it includes both kinds of sounds. Indeed, the array of resources available to contemporary musicians working in the medium of electroacoustic music is an impressively rich and immense one . . . .

Samuel Pellman, An Introduction to the Creation of Electroacoustic Music xv (Wadsworth 1994).

Earlier this month, Pellman died suddenly at the age of sixty-four.

Here is an example of his recent work:

Sam’s Music for Contemporary Media course remains one of the most memorable educational experiences of my life. I offer here two of the projects I created as a part of that course.

In re Monster Mash

In 2017’s internet-centric media world, the illusion of interactivity trumps truth, and the mind-altering pursuit of that illusory activity has little time for factual accuracy. Thus, it was with familiar disappointment that I encountered the below stitch of web content in the days preceding the instant holiday:

I do not know Lawrence Miles. There is a good chance I do not know any of the roughly sixty thousand internet people who interacted with Miles’ tweet. I do know “Monster Mash,” though.

“Monster Mash” is at least two things: 1) a song recorded and released by Bobby “Boris” Pickett and The Crypt-Kickers in 1962 and 2) a dance performed by the monsters referenced in the song.

Miles’ statement obviously is incorrect on its face. After all, Pickett’s song, which topped charts shortly after its release and remains a seasonal favorite more than sixty years later, has reached many ears.

Of course, that is not the sense at which Miles directed his tweet. The song may be called “Monster Mash,” but it certainly is about something called “the monster mash” as well, and that subject is Miles’ target. Miles may not be a careful listener, however, because the song clearly identifies and describes the monster mash as a dance, rather than a song:

I was working in the lab, late one night

When my eyes beheld an eerie sight

For my monster from his slab, began to rise

And suddenly to my surpriseHe did the mash, he did the monster mash

The monster mash, it was a graveyard smash

He did the mash, it caught on in a flash

He did the mash, he did the monster mashFrom my laboratory in the castle east

To the master bedroom where the vampires feast

The ghouls all came from their humble abodes

To get a jolt from my electrodesThey did the mash, they did the monster mash

The monster mash, it was a graveyard smash

They did the mash, it caught on in a flash

They did the mash, they did the monster mash

There is no ambiguity here. Whether it was the monster mash or the mashed potato, the narrator is describing a particular dance the monsters were doing, not a song they were playing. Miles reasonably might have contended that no one had ever seen the monster mash dance performed, but his statement, insofar as it contemplates the monster mash as a song, finds no support in the text itself.

A potential problem for the analysis presented in this post appears in the chorus following the third verse, however, which uses slightly different phrasing:

The Zombies were having fun, the party had just begun

The guests included Wolfman, Dracula, and his sonThe scene was rockin’, all were digging the sounds

Igor on chains, backed by his baying hounds

The coffin-bangers were about to arrive

With their vocal group, ‘The Crypt-Kicker Five’They played the mash, they played the monster mash

The monster mash, it was a graveyard smash

They played the mash, it caught on in a flash

They played the mash, they played the monster mash

A band appears and, for the first time, this chorus introduces the notion that the monster mash is something that could be “played” as well as done, lending apparent support to the implied premise of Miles’ assertion (i.e., that the monster mash is a song). At this juncture, the best we can do is meet Miles part way. The monster mash plainly is a dance, but it might also be a song. If so, however, the question remains: have we heard the monster mash song?

With an assist from Dracula, the monsters answer this question in the affirmative. Immediately after the foregoing chorus, the narrator tells us:

Out from the coffin, Drac’s voice did ring

Seems he was troubled by just one thing

He opened the lid and shook his fist and said

“Whatever happened to my Transylvania Twist?”It’s now the mash, it’s now the monster mash

The monster mash, it was graveyard smash

It’s now the mash, it caught on in a flash

It’s now the mash, it’s now the monster mash

Importantly, Dracula has been in his closed coffin this entire time (“Out from the coffin . . . He opened the lid . . .”), so he had not seen the monster mash dance but he had heard the monster mash song. Thus, when he asked about the “Transylvania Twist,” now rebranded as “The Monster Mash,” he was referring to a song and not a dance. And, contrary to Miles’ claim, we have heard “Transylvania Twist,” a rollicking barrel-house instrumental that would sound right at home in Eastern Kentucky:

No matter which way you slice it, Miles was wrong: the monster mash is a dance, and, to the extent it also is a song, it is a song we have heard.

(While the preparation of this post brought me no pleasure, I was glad to learn in the course of my research that the late Leon Russell was a Crypt-Kicker whose keyboard mashing appeared one one of the tracks on The Original Monster Mash, “Monster Mash Party,” which was the b-side to “Monster Mash.”)

Wishing everyone an honest Halloween.

Balloon Mortgage

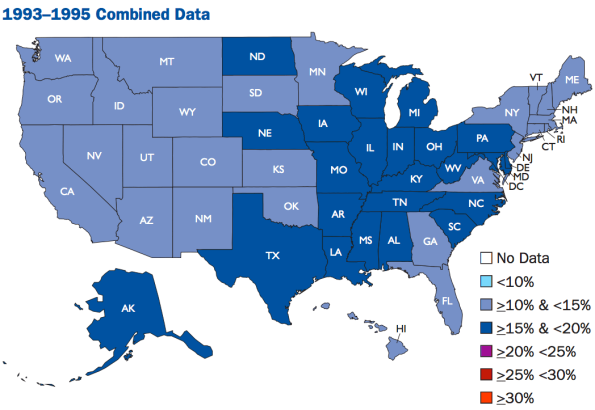

When people look at United States obesity statistics, they mostly seem to enjoy those presented in map format, with state-by-state breakdowns, maybe because they like to make fun of people who live in other (or maybe certain) places. Here’s one of those maps:

Obesity, like most matters of a biological nature, is a complicated subject. On a nationwide basis, though, at least among adult Americans, the trend is fairly clear:

If one grants the premise that we know more about nutrition and fitness now than at any prior point, the ever-increasing adult obesity rates seem to confound. Perhaps the slight divergence in youth obesity rates is an indication of the societal internalization of this health education. Perhaps obesity simply is a complicated subject.

For Want of a Better Protest

Seven years ago, I wondered here whether America might be in need of a more meaningful, perhaps even physical, flavor of civic engagement. Stretching a bit, perhaps, I wrote:

The peak of this time of civic unrest, the late 1960s, has become an archetypical reference point for much of the subsequent civic and political action. The question now is whether this model has been stretched too thin, overused, and, in a certain way, too peaceful, in the age of the internet. Is web-based “social networking” the sort of engagement and participation that would impress Tocqueville, Kennedy, King, Putnam, or Armstrong? Are 140 characters enough for a meaningful treatise? Can a Facebook.com group change the world? Or should we just grab a groupon and plan our revolutions face-to-face at the newest eatery (that checks out on Yelp, of course)? In short, global electronic connectivity has fostered the rise of a sort of wide-sweeping, possibly disparate civic engagement, but is it of significant consequence? Have we walked too far away from the days of settling our differences and sorting things out on the battlefield?

Since then, the reelection of President Barack Obama and the subsequent election of President Donald Trump have preceded and likely fueled an increased attention to and participation in civic engagement and public discourse, at least of a certain variety. It remains to be seen whether this allegedly newfound brand of political participation is politically effective or merely serves to enhance the (digital and corporeal) egos of the participants.

Yesterday, the New York Times published an interview with Ed Cunningham, a person whose name probably is known to few, but whose voice may be more recognizable, memorializing a sort of retirement signing statement from the now-former ABC and ESPN college football broadcaster who apparently resigned this spring but did not disclose the real reason for his resignation, he says, until now: he believes football is a dangerous sport.

In its current state, there are some real dangers: broken limbs, wear and tear. But the real crux of this is that I just don’t think the game is safe for the brain. To me, it’s unacceptable.

Cunningham feels his job placed him in “alignment with the sport. I can just no longer be in that cheerleader’s spot.”

First, the timing of Cunningham’s explanation is curious not because it is coordinated with the beginning of the current college football season in order, one assumes, to deliver maximum media impact, but because it did not come years ago. The sport’s governing bodies at the scholastic and professional levels may, like tobacco companies before them, continue to distance themselves from reports and research on the relationship between football and brain damage, but whatever popular science concepts informed Cunningham’s decision are not new.

Second, to the extent Cunningham is fashioning his resignation as a protest designed to effect change in the sport, his approach seems shortsighted. In surrendering his national media platform, Cunningham has traded the opportunity to discuss the issues he claims are so important to him with a relevant audience on a regular basis for the chance to fire a single bullet– yesterday’s article– before disappearing from public sight. If his goal was to make football safer, surrendering an important resource does not seem like the best way to accomplish that goal. Even if he was worried that his superiors would not permit him to make the sort of (pedestrian, frankly) comments he provided to the Times during game broadcasts, it would have made for a more broadly significant departure from his position had a network (i.e., a league “broadcast partner”) terminated him for making those or similar statements. As it stands, someone else simply will replace him, and everyone will move on. The article quotes Al Michaels, a much more prominent football broadcaster:

I don’t feel that my being part of covering the National Football League is perpetuating danger. If it’s not me, somebody else is going to do this. There are too many good things about football, too many things I enjoy about it. I can understand maybe somebody feeling that way, but I’d be hard-pressed to find somebody else in my business who would make that decision.

In an effort to be fair to Cunningham, it is not completely clear from his actual statements quoted in the article whether he made his decision for the purpose of making football safer or for the personal purpose merely of extracting himself from an endeavor he now believes is too dangerous for his participants. Knowing the probable effect of telling his story the way he did, the distinction may be of no significance. If he wanted to be a source of meaningful change, though, Cunningham should have made like his contemporary version of Alexander Hamilton and stayed on his microphone as long as possible. Instead, he’s done just enough to satisfy his own guilt through effortless moral posturing. In that, he is not a unique player in today’s civic arena, but worthy causes deserve more.

Toward an Expanded Right to Legal Counsel

In declaring America’s independence, the emerging nation’s founding fathers included this memorable statement of principle:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

In further recognition of the unalienability of these rights, the Constitution itself provides for a guarantee of legal assistance when faced with the judicial deprivation of life or liberty:

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to . . . have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

Const. Am. VI.

The Sixth Amendment’s affirmative provision is robust and significant, but it attends only to two of the three unalienable rights identified in the Declaration. Of course, that third right, “the pursuit of Happiness,” is, at least on the surface, little more than a Jeffersonian flourish. It barely disguises the origin of the complete statement of rights, however, which Jefferson borrowed from John Locke, the English political philosopher, who referred to the importance of protecting individual’s life, liberty, and property.

If the Constitution protects us– by way of the right to legal counsel– when the government threatens to deprive us of life or liberty, shouldn’t that right also extend to deprivations of property?

United States governing bodies at the federal, state, and local levels continue to exercise their authority to take private property by eminent domain, a legal theory derived from the British concept of the divine right of the monarch. The Constitution, in the Fifth Amendment, demands that the government afford individuals both due process and just compensation in such instances, but there is no express right to legal counsel in order to help guarantee the protection of those Fifth Amendment rights of individuals facing eminent domain takings. If we truly regard property rights as unalienable as our rights to life and liberty, shouldn’t the protective right to legal counsel be extended to cover all three?

The Department of Education in the Age of “Hamilton”

I wrote this headline back in December, along with the note “federalism” and a link to an editorial criticizing Donald Trump’s nomination of Betsy DeVos for the position of Secretary of the U.S. Department of Education. Surprisingly, seven months later, those two breadcrumbs were not enough to lead my brain back to the space it occupied at that particular moment. The “Hamilton” connection I had in mind likely will continue to escape me, but I think the basic point probably went something like this:

For those who prefer a smaller federal government, the Department of Education is a popular target. The basic line of thought seems to be that public education traditionally has been the province of the individual state governments, and that it is ineffective to try to set uniform national policies when it comes to public education. Perhaps as a result of that targeting, or perhaps for independent reasons (and likely a combination of both), those who favor a more expansive federal government also favor a strong Education Department, believing it is the best vehicle for preserving and supporting the public school system and for bringing what they see as outdated education policies (particularly in the area of school curriculum) in line with modern standards.

For those who prefer a smaller federal government, the Department of Education is a popular target. The basic line of thought seems to be that public education traditionally has been the province of the individual state governments, and that it is ineffective to try to set uniform national policies when it comes to public education. Perhaps as a result of that targeting, or perhaps for independent reasons (and likely a combination of both), those who favor a more expansive federal government also favor a strong Education Department, believing it is the best vehicle for preserving and supporting the public school system and for bringing what they see as outdated education policies (particularly in the area of school curriculum) in line with modern standards.

For the latter group, one problem with consolidating power in a single, central office, of course, is that there may come a time when the person who occupies that office does not share that group’s policy preferences. This somehow seems to be a point of cognitive disconnect for this group, which does not appear to have considered the possibility that a political opponent like DeVos might one day occupy the office of the Secretary of the Department of Education and use the substantial authority attached to that office to advance her own policy preferences.

Politics ultimately may be a game of short-term gains, but the cries of those bemoaning Secretary DeVos’ newfound ability to support a deregulated charter school movement and other school-choice plans because they believe those policies will undercut already-struggling public schools ring at least partially hollow; after all, they bear some responsibility for the expanded scope of her authority to do so.

Book Review: Powerhouse: The Untold Story of Hollywood’s Creative Artists Agency

Along with Tom Shales, James Andrew Miller previously published two book-length oral histories of large American entertainment institutions that originated in the 1970s, ascended to the peaks of their respective spheres of influence, and persist as significant players in the entertainment landscape today. The subjects of those two books, ESPN and Saturday Night Live, also retail their content directly to their public audiences. For the third book in this series of sorts, Miller, now on his own, turns his focus to Creative Artists Agency, an entity that matches all of the same characteristics of ESPN and SNL sketched above save one: it is an insider, a talent agency that works (sometimes barely) behind the scenes to conduct the business of the entertainment industry and, thereby, indirectly influence the entertainment we all consume.

Along with Tom Shales, James Andrew Miller previously published two book-length oral histories of large American entertainment institutions that originated in the 1970s, ascended to the peaks of their respective spheres of influence, and persist as significant players in the entertainment landscape today. The subjects of those two books, ESPN and Saturday Night Live, also retail their content directly to their public audiences. For the third book in this series of sorts, Miller, now on his own, turns his focus to Creative Artists Agency, an entity that matches all of the same characteristics of ESPN and SNL sketched above save one: it is an insider, a talent agency that works (sometimes barely) behind the scenes to conduct the business of the entertainment industry and, thereby, indirectly influence the entertainment we all consume.

Miller’s Powerhouse: The Untold Story of Hollywood’s Creative Artists Agency follows the same structure he and Shales used in the ESPN and SNL books, which generally track a chronological arc and tell their tales through the words of those involved, directly or tangentially, with the subject, with only brief editorial interludes to organize and move the story along. As an example, a page from the ESPN book illustrates the approach:

For whatever reason, or set of reasons, the CAA book does not work as well as the previous Miller-Shales collaborations. Miller promises to reveal the most powerful man in Hollywood, Michael Ovitz, his philosophically balancing counterpart, Ron Meyer, and the revolutionary agency they built together, CAA, that, at its mid-1990s peak, had the entertainment industry in the palm of its hand and made gobs of money for its owners and employees. That is Miller’s headline, and the sub-lede would explain that Ovitz drew power to himself with a combination of a politician’s natural networking skills and near-unbridled ambition; Meyer countered Ovitz’s cold, calculating approach with heart, emotion, and honesty; and CAA succeeded by developing a “packaging” model that allowed them, for example, to sell a cast of actors they represented to a director they also represented to make a movie written by a screenwriter they also represented– at its best, vertical and horizontal integration– such that CAA could be on all sides of a deal it created and even financed.

It may be because I am not a movie buff and do not track celebrity gossip magazines, but I did not take much from this book beyond the basic summary outlined above and in the interviews I heard with Miller prior to reading it. At a minimum, the book needed at least one more editorial pass before publication to correct what I interpreted as organization problems, including quotations appearing multiple times in the book and editorial interludes that introduced topics unaddressed by the subsequent quotations or merely summarized the ensuing quotations and borrowing the subjects’ same descriptive words.

More broadly, the contents did not do a great job of developing the depth of the main characters. Ovitz understandably is the primary focus, but we learn little of his backroom dealings, for example. There are surprisingly few stories about Meyer, the supposed counterweight to Ovitz, and Bill Haber, the other CAA founder who spent a significant number of years with the company, is left twisting in the wind, hanging onto little more than an adjective card that has the word “eccentric” written on it. Also due for more attention, one would have expected, is the late-arriving Sports (capitalized, for some reason) division of the agency, which now appears to be floating the company financially. Finally, Ovitz’s replacement, current CAA president Richard Lovett, has very little to offer about the present state and trajectory of the company beyond reliably optimistic soundbites.

Again, I likely am not in the target audience for this book, and I would not be surprised if those closer to Hollywood and with a longer-running experience in or familiarity with the entertainment business enjoyed and learned from it. It is possible that Miller did not probe his subjects forcefully enough; independently, it is possible that the subjects simply refused to speak more openly (Sylvester Stallone, whose comments appear throughout the book, apparently had few such qualms). At a minimum, however, the book would benefit from a greater attention to organizational detail. It just came out in an updated paperback edition, though, so that may address some of these concerns.

Latest Comments